My father died in 1980, aged sixty-six, weeks after the opening of a major retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Fortunately, he had lived to see his late figurative work, critically rejected for a decade after it was first exhibited, begin to generate real interest.

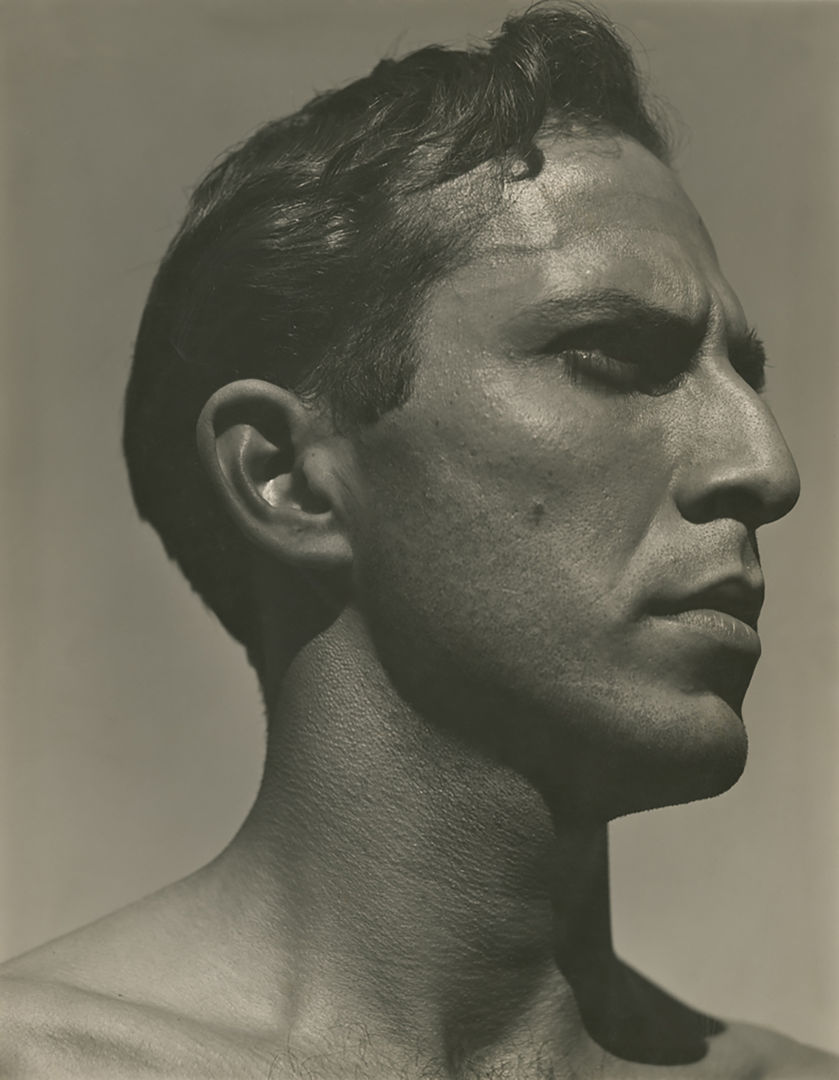

Philip Guston at age sixteen, in 1929. Photograph by Leonard Stark

There had always been works he didn’t want to sell, the letters N.F.S. (“not for sale”) in his own hand on the backs of canvases and framed drawings. In a choice that now seems prescient, my mother, Musa McKim Guston, and I added to his N.F.S. list in the years after his death, curating a collection of works representative of the entire fifty years of his career that could be loaned to retrospectives and survey exhibitions. We knew that once in private hands, important works might be “lost” to public view. We wanted to ensure that Philip Guston’s art would always be seen and appreciated in its full scope. Over four decades, the N.F.S. collection has been a crucial lending collection. Many of these works are currently on display in the retrospective exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. through August 27, 2023.

Philip Guston (American, born Canada, 1913–80). Mother and Child, ca. 1930. Oil on canvas, 40 x 30 in. (101.6 x 76.2 cm). Promised Gift of Musa Guston Mayer to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photograph by Genevieve Hanson

I’ve always believed that my father’s art belongs to the world. On the advice of David McKee, who represented my father’s work for forty-one years, both before and after his death, my mother made provisions in her will for bequests of more than one hundred paintings to be given to seventy-five carefully chosen public museums around the United States. Upon her death in 1992, we were able to secure deaccessioning agreements from all but one of the museums. In addition, over the forty-three years since my father’s death, I’ve given hundreds of Guston paintings, drawings, and lithographs to museums in the United States and Europe.

As I approached my eightieth birthday, I worried about what would happen to the N.F.S. lending collection after my husband and I were gone. I began weighing alternatives. Times had clearly changed in the museum world, particularly in recent years. Undertaking another broad distribution of works would have been challenging. A negotiation of display requirements or deaccessioning would likely no longer be possible.

Philip Guston (American, born Canada, 1913–80). Untitled, 1980. Acrylic and ink on illustration board, 20 x 30 in. (50.8 x 76.2 cm). Promised Gift of Musa Guston Mayer. Photograph by Genevieve Hanson

Nor did I want to split up these works among different museums. We had selected the collection with a single goal in mind: to represent a coherent selection of Guston’s art from 1930 to 1980. Since continual transformation was so characteristic of my father’s career, it was essential to document the process of exploration and questioning that often confounded his critics.

Documenting these transformations led us to include several preparatory drawings and paintings. Examples are the so-called “alphabet” panels from 1968–70, never exhibited separately, which constitute fully a third of the ninety-six paintings in the N.F.S. collection. Other works are primarily of scholarly interest, detailing the early years of my father’s career. Still others represent examples of diverse pursuits, the so-called “pure” drawings of 1967, or his Nixon caricatures from 1971.

Installation view of Philip Guston Now (October 23, 2022–January 16, 2023) at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, featuring several “alphabet” panels and, at center, The Studio (1969). Photograph by Thomas R. DuBrock. Courtesy the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

The Guston Foundation was formed in 2013 to secure my father’s legacy: to catalog his art and archival materials, facilitate publications and exhibitions, and develop a website where my father’s life and work would be freely accessible to everyone. Today our website hosts a searchable catalogue raisonné of paintings, exhibitions, museum collections, and bibliography, as well as slideshows, a scrapbook, and an extensive chronology of his life. At first, the Guston Foundation seemed like the natural home for the N.F.S. collection. But questions crept in: What would happen over time? How could I be sure that the best decisions for such an important and valuable collection would be made, given escalating costs of insurance, art storage, and conservation?

Since continual transformation was so characteristic of my father’s career, it was essential to document the process of exploration and questioning that often confounded his critics.

A dedicated Philip Guston Museum was the least desirable option. My father would never have wanted a pilgrimage site dedicated solely to his art. His restless innovation had isolated him long enough. And he loved the great museums of the world, especially The Met, which had been part of our lives since I was a little girl. I felt certain he would want his work to be seen in the company of other great art of all historical periods, that he would be honored to be among the masters he so revered.

Philip Guston (American, born Canada, 1913–80). Pantheon, 1973. Oil on panel, 48 x 45 in. (121.9 x 114.3 cm). Promised Gift of Musa Guston Mayer. Photograph by Genevieve Hanson

The Met was first on my list. Several factors gave me the courage to initiate a conversation with Max Hollein. As director of the Schirn Kunsthalle, he had hosted a Guston survey in Frankfurt, and he had spoken at a recent Guston symposium. Under his leadership, the new wing for modern and contemporary art was finally going to be built, after years of delays. With the increased exhibition space, I dared to hope that the Museum might be interested in enhancing their collection of mid-twentieth-century art. The Met’s tradition of scholarship and depth of curatorial experience was a strong incentive as well. To my delight, when I approached Max, there was immediate interest in the N.F.S. collection and we began to discuss the terms of our agreement.

The promised gift contains a balanced group of paintings and drawings that cover an entire fifty-year career, carefully selected to complement The Met’s existing collection of Philip Guston. The extensiveness of the gift offers curators at The Met the opportunity to display the works with others in their collection, anywhere in the museum, for maximum curatorial flexibility.

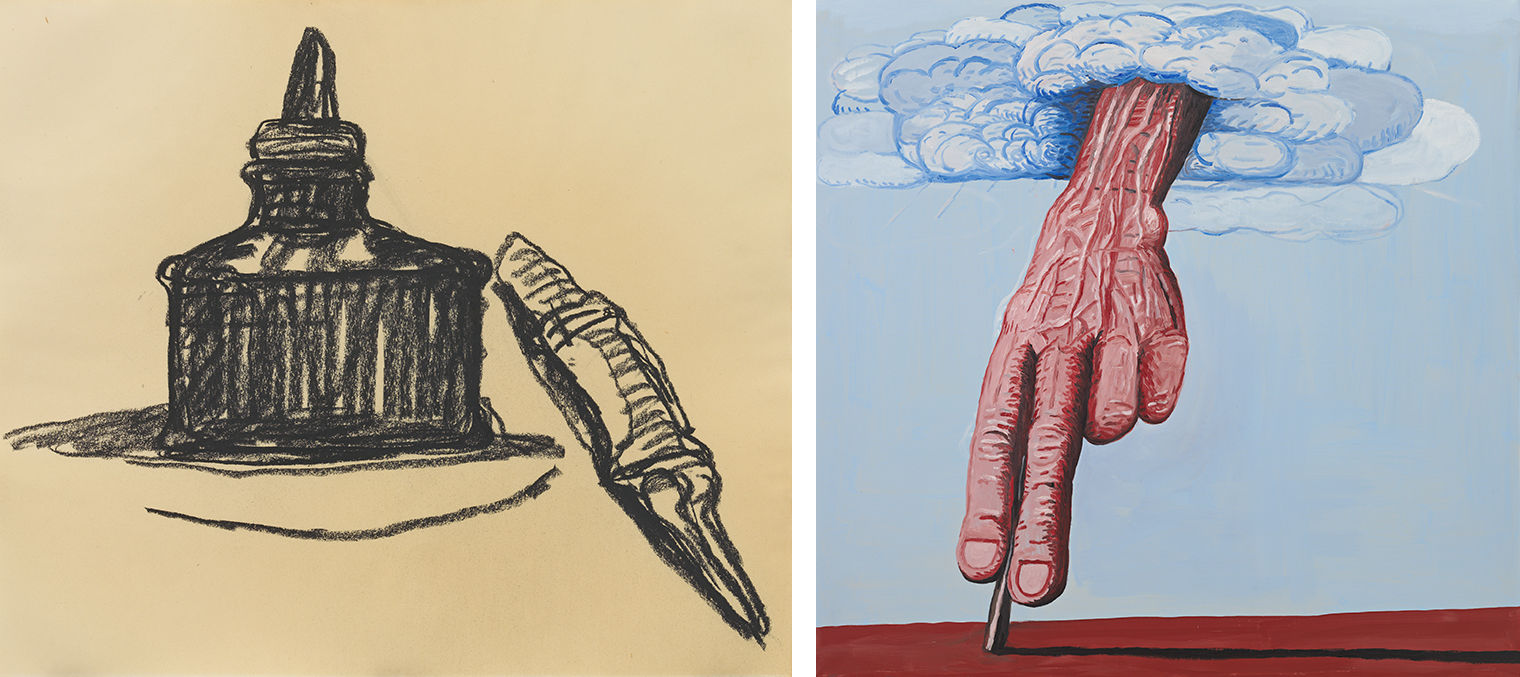

Left: Philip Guston (American, born Canada, 1913–80). Ink Bottle and Quill, 1968. Charcoal on paper, 14 x 16 1/2 in. (35.6 x 41.9 cm). Promised Gift of Musa Guston Mayer. Right: Philip Guston (American, born Canada, 1913–80). The Line, 1978. Oil on canvas, 71 x 73 1/3 in. (180.3 x 186.1 cm). Promised Gift of Musa Guston Mayer. Photographs by Genevieve Hanson

The two hundred twenty works assembled in the gift extend far beyond the best-known major works. Of the ninety-six paintings, more than a third are 18 x 20 inches or smaller. There are also a substantial number of drawings and paintings whose value can be described primarily as art historical, included to contribute to the study of Guston’s development as an artist and to tell his story. Scholarship about the artist is an important part of my goal for this gift, so to have these works available for that purpose is critical. In conjunction with the continuing legacy work of the Guston Foundation, this gift to The Met will serve to centralize the study of the works and career of a great artist, for which we have also created an endowment. A key part of the agreement stipulates an openness to loans to other museums and galleries who wish to exhibit Gustons from this collection. While images of all my father’s works are available online, the physical presence of the works themselves is crucial.

Left: Philip Guston (American, born Canada, 1913–80). Untitled, 1980. Acrylic and ink on illustration board, 20 x 30 in. (50.8 x 76.2 cm). Promised Gift of Musa Guston Mayer Right: Philip Guston (American, born Canada, 1913–80). Untitled, 1980. Acrylic and ink on illustration board, 20 x 30 in. (50.8 x 76.2 cm). Promised Gift of Musa Guston Mayer. Photograph by Genevieve Hanson

Listening to younger artists describe Guston’s importance to their own work has led me to a deeper appreciation of the nature of that influence, and why, so many years after his death, his life and work still matters so much to so many. This influence transcends style or specific figuration—although clearly his late work in the 1970s helped initiate a new figuration in painting at a time when abstraction was dominant. Many find inspiration in Guston’s passion and deep engagement with the act of painting, the physicality of his surfaces, his love of the medium, and the history of painting throughout the ages. My father’s insistence in following his own path, regardless of consequences to his career or reputation within the art world, is seen by many artists as courageous, even empowering. He was always questioning his work, challenging the enterprise of painting, opening himself to the pain and ugliness of the world, allowing the transformations he considered essential. His value as an influence on younger painters derives from this inner challenge, which he shared so openly with others.

Philip Guston teaching with students at Boston University in 1978. Image courtesy The Guston Foundation

Speaking at the Yale Summer Art School during the 1970s, my father prefaced a slideshow of works from his entire painting life by saying: “Some of you may think, why all these changes? It has taken me years to come to the conclusion that probably the only thing that one can learn—you know, we talk about techniques—I think the only technique we can learn is the capacity to be able to change. And it’s a very difficult thing. But as modern artists that’s our fate: constant change. I don’t mean novelty or anything like that. What I mean is that this serious play that we call art, can’t be static. You have to keep learning how to play in new ways all the time.”

All artworks © The Estate of Philip Guston. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Marquee: Philip Guston (American (born Canada), 1913–1980). Painter's Hand (detail), 1975. Oil on canvas, 67 x 79 in. (170.2 x 200.7 cm). Promised Gift of Musa Guston Mayer. Photograph by Genevieve Hanson